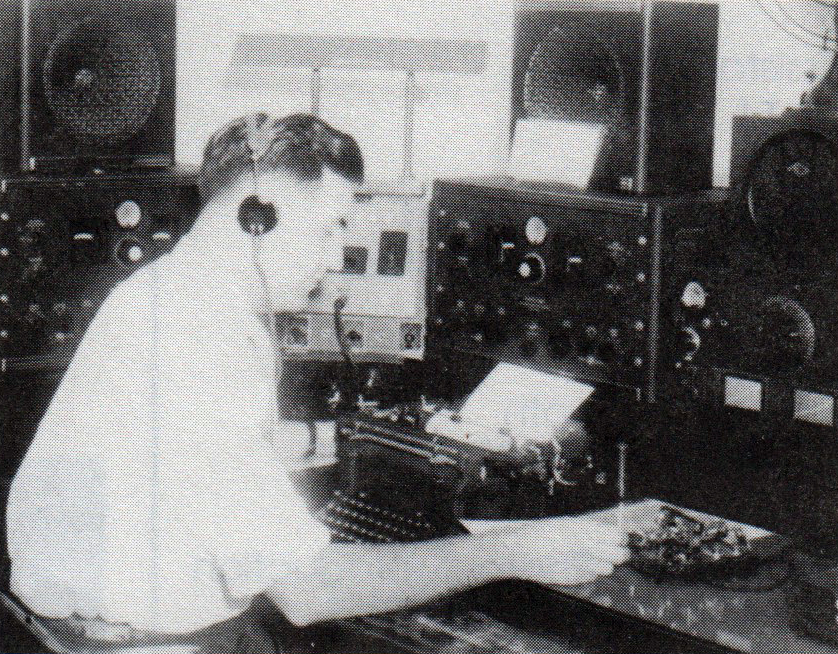

Dwayne L. Eskridge at controls of Honolulu radio station in 1941.

For 132,000,000 Americans living at the time, the start of a new decade in 1941 brought hope that that their lives would soon improve. The population had been through all too many years of challenging times thus far in the 20th Century. It had experienced World War I (then referred to as the Great War of 1914-1918), the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 to 1920, espionage, sabotage, terrorism, Prohibition, the Gangster Era, or the wrenching economic effects of a stock market crash and the Great Depression all had taken place. The Nation was badly shaken but still stood strong, things were improving for many people, and prospects looked better than they had in a long time. Advances in technology, inventions, medicine, the New Deal, the reelection of a President for an unprecedented third tour-year term.

Yet, there was some sense of uneasiness. Nothing could be certain. Europe already was engaged in a brutal war and had been for over a year, but the conflict was an ocean away. Tensions and warfare were rising in Asia, but that also was located another ocean away. There was hope that the United States would not be drawn into another overseas conflict anywhere at any time.

Nonetheless, the FBI, as well as the military and other government agencies, was mindful of threats. Its intelligence and investigative personnel were active and on alert.

The FBI Enhances Its Shortwave Radio System

In addition to its other work, the FBI was concentrating on an important project which would use powerful, high-frequency shortwave radio equipment and antennas, to link FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC and as many of its field offices as possible. In particular, offices outside the continental 48 States—in Honolulu, Juneau, and San Juan—would be given top priority for the radio installations.

In this era before satellites, shortwave radio was the powerful and reliable option to get a signal through when other technology could not. The British already had experienced great disruptions in their telephone and telegraph capabilities thus far in World War II from German attacks, a weak link the FBI wanted to avoid.

The FBI had been constructing its shortwave radio system since 1937, and the work was being managed by its Laboratory Division at FBI Headquarters. The Special Agents, technicians, and engineers there had the most experience with both radio technology in addition to forensic analysis of evidence. It was the logical administrative location for the radio staff. The FBI already had hired two professional radio operators who were skilled with sending and receiving Morse Code messages at very high speed. One of them, James Corbitt, soon enough would handle the biggest radio messages of his life.

Melvin Barrett operating the radio station, WFBN, in the FBI’s Honolulu Office, 1942.

In mid-1941, the FBI already had constructed a shortwave radio station on a cliff overlooking the Chesapeake Bay 35 miles southeast of downtown Washington, DC. The Bay Station Chesapeake, as it was called, was capable of sending and receiving messages from England, San Juan, and South America. Now, the focus shifted to setting up radio stations in Alaska, Hawaii, and on the West Coast. Another location on a cliff overlooking a body of water, the Pacific Ocean, was selected in San Diego, California, on an estate with the permission of the owner.

In the summer of 1941, Mr. Corbitt was assigned to work at the new San Diego facility and was joined by a newly hired employee named Dwayne Eskridge. Originally from Arizona, Mr. Eskridge was teaching school when he learned of a job opportunity with the FBI. Due to his familiarity with shortwave radios due to his hobby of ham radio and knowledge of Morse Code, he was assigned to the FBI Laboratory. Within weeks, Mr. Eskridge was sent to work on setting up the radio station in San Diego.

The Hallicrafters HT-4 / BC-610

A shortwave radio system in 1941 used by military, government, commercial, and ham radio operators usually consisted of a separate receiver and a transmitter with and assortment of glowing vacuum tubes inside. Equipment made in the United States commonly was manufactured by companies named Hallicrafters, Hammarlund, and National. A Hallicrafters HT-4 transmitter console weighing over 350 pounds and measuring about two feet by three feet was used at the San Diego and Honolulu stations. It could transmit a signal of 300 watts in AM voice and 400 watts CW (Morse Code). Such signal strength even today is considered powerful. Receivers were about the same dimensions. Antennas were lengths of tubular metal or copper wire cut to specific resonant lengths, usually erected on rooftops or some distance off the ground on poles or towers. Radio stations were powered by normal household electrical voltage. The stations also had a telephone land line and a teletype machine.

It would take some expertise to make the station operational. Messrs. Corbitt and Eskridge were joined at the San Diego location by a supervisory FBI Special Agent from the FBI Laboratory named Ivan W. Conrad. Once the work was completed, Mr. Corbitt remained to be the chief operator of the station and it was time for two of them to travel to the next installation job in Honolulu, in what then was the distant Territory of Hawaii. (The Territory would not become a State until August 1959, the 50th.)

The FBI’s Radio Station in Honolulu is Established

Messrs. Eskridge and Conrad sailed for Honolulu in mid-November 1941 and arrived in a few days. But there was an obstacle to overcome. A suitable remote location was not available to the FBI in or near Honolulu.

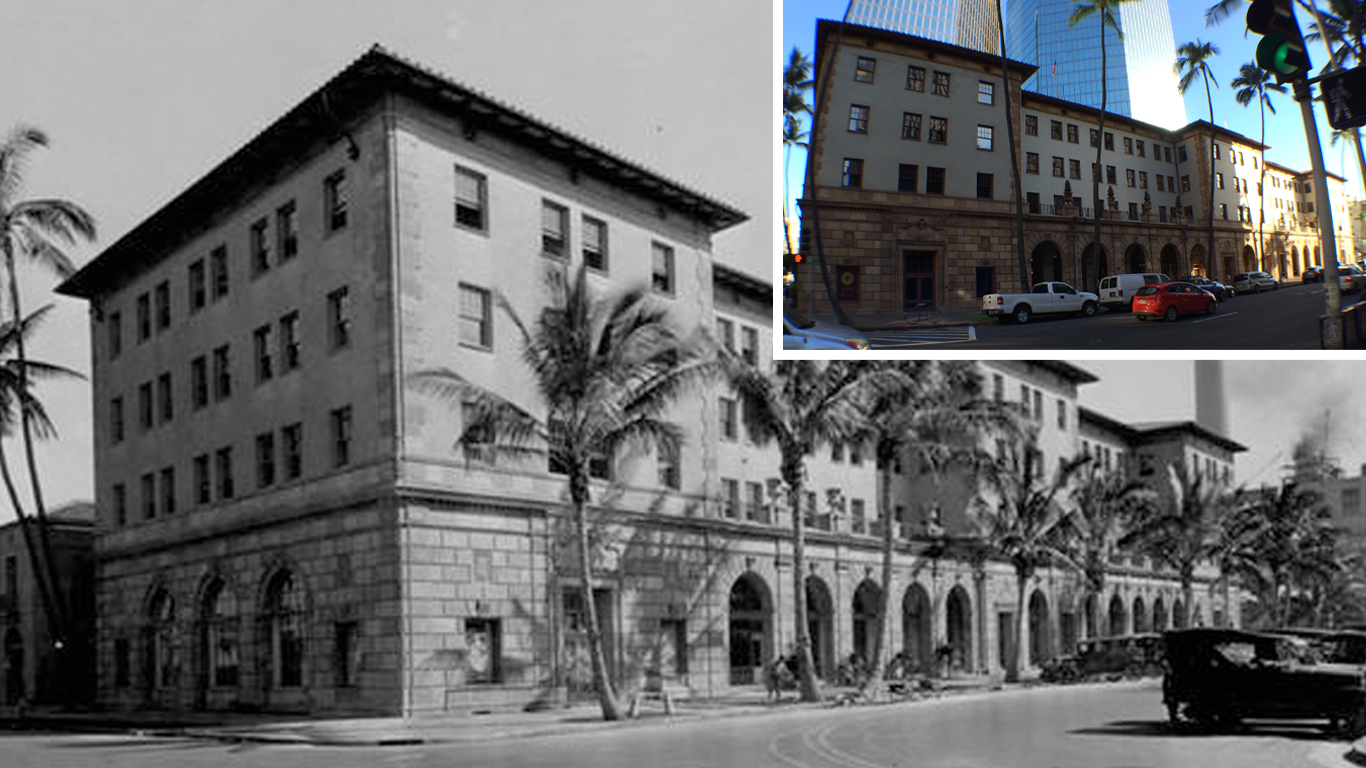

The FBI’s Honolulu Field Office was comfortable but not spacious. Located on the second floor of the three-story Dillingham Building on Bishop Street (the building still exists today although the FBI Field Office is located elsewhere), the antenna would have to be placed on the building’s roof. The radio equipment would need to be installed and operated in the office’s firearms and storage room. It would have to do. Most importantly, the field office was in a suitable location for receiving and transmitting shortwave radio signals. There were no tall structures close by, and the only major activity was located six miles away. At the military base at Pearl Harbor.

Despite the initial challenges, the installation of the transmitter, receiver, antenna, cables, and related items went very well. Test radio messages between the Honolulu and San Diego stations covered the 2706 miles between them clearly despite the usual fluctuations in transmission and reception caused by atmospheric conditions, time of day, sunspot cycle patterns, and weather. In fact, the work went well enough to enable Mr. Conrad to return to Washington, D.C. in late November. Mr. Eskridge would finish the work and testing, then return to the United States on Tuesday, December 9.

The Dillingham Building (foreground), circa 1942. The Honolulu Office was located on the second floor.

To assure his work would be done by his scheduled departure date, Mr. Eskridge decided to work on Sunday morning, December 7, and to get to the office early. He switched on his radio equipment and began sending test messages at 7:30 a.m. on a prearranged shortwave frequency to Mr. Corbitt. Mr. Eskridge was using the call sign letters WFBN and Mr. Corbitt was using WFBB.

The FBI Radio Systems Are Put to the Test

The two radio operators were exchanging routine communications when their lives abruptly changed, along with the lives of millions of others that morning. Japanese airplanes were bombing ships and installations at Pearl Harbor. Shortly after the attacks began at 7:55 a.m. local time, a Honolulu employee on duty, Franklin Sullivan, ran to the radio station in the storage room to tell Mr. Eskridge that a telephone call had just come in about the attacks. The two of them rushed to the roof of the Dillingham Building and saw scores of Japanese airplanes, the first of the 353 aircraft that would descent in two waves that morning. The airplanes were flying so low and slow in their approaches that the pilots could be seen clearly in their cockpits. Noise from the bombs, and the resulting explosions, fires, and smoke, even at a distance, were tremendous.

Mrs. Eskridge stayed only briefly on the roof. He knew he had to get the word out, and he the means at his disposal. The radio system would get its first test in a crisis. He ran back to his radio station and tapped out a message at 8:30 a.m. local time:

“WFBB from WFBN, if you are still there, stand by for very urgent and important message.” Mr. Eskridge tensed during the moment it would take for his message to be received and acknowledged. He was relieved to hear a response from the speaker of his receiver and informed an astonished Mr. Corbitt about the attack. The FBI San Diego Field Office was notified by telephone, who in turn telephoned FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC.

Mr. Eskridge’s first radio message to Mr. Corbitt was among several initial messages about the attack sent from Hawaii by the U.S. military of civilians via radio or telephone. According to written accounts, the first word of the attack was transmitted at 7:58 local time by radio operators at Pearl Harbor at the direction of U.S. Navy Lt. Commander Logan Ramsey that became famous: “AIR RAID PEARL HARBOR. THIS IS NO DRILL.” This message was received 22 minutes later in the Nation’s Capital, where the time zone difference of 5.5 hours in those days meant the message was received about 1:50 p.m.

The exact times of transmission and receipt of all messages about the attack are not known, although it is certain that the radio message sent by Mr. Eskridge and received by Mr. Corbitt was the first notification to reach the FBI.

Later in the morning of December 7, in an oft-repeated story within the FBI, Robert Shriver, the Special Agent in Charge of the Honolulu Field Office, reached FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover by telephone to update him. Director Hoover was in New York City and was able to hear explosions from the bombing in the background.

Despite the existence of the telephone capability, the Honolulu shortwave radio station often was the only secure, reliable means of communication for the FBI in the critical early days of the war. Military communications facilities were overwhelmed by their own radio traffic, and commercial facilities were frequently disrupted. The value of the new shortwave radio system was obvious, and Messrs. Corbitt and Eskridge instantly had become indispensable.

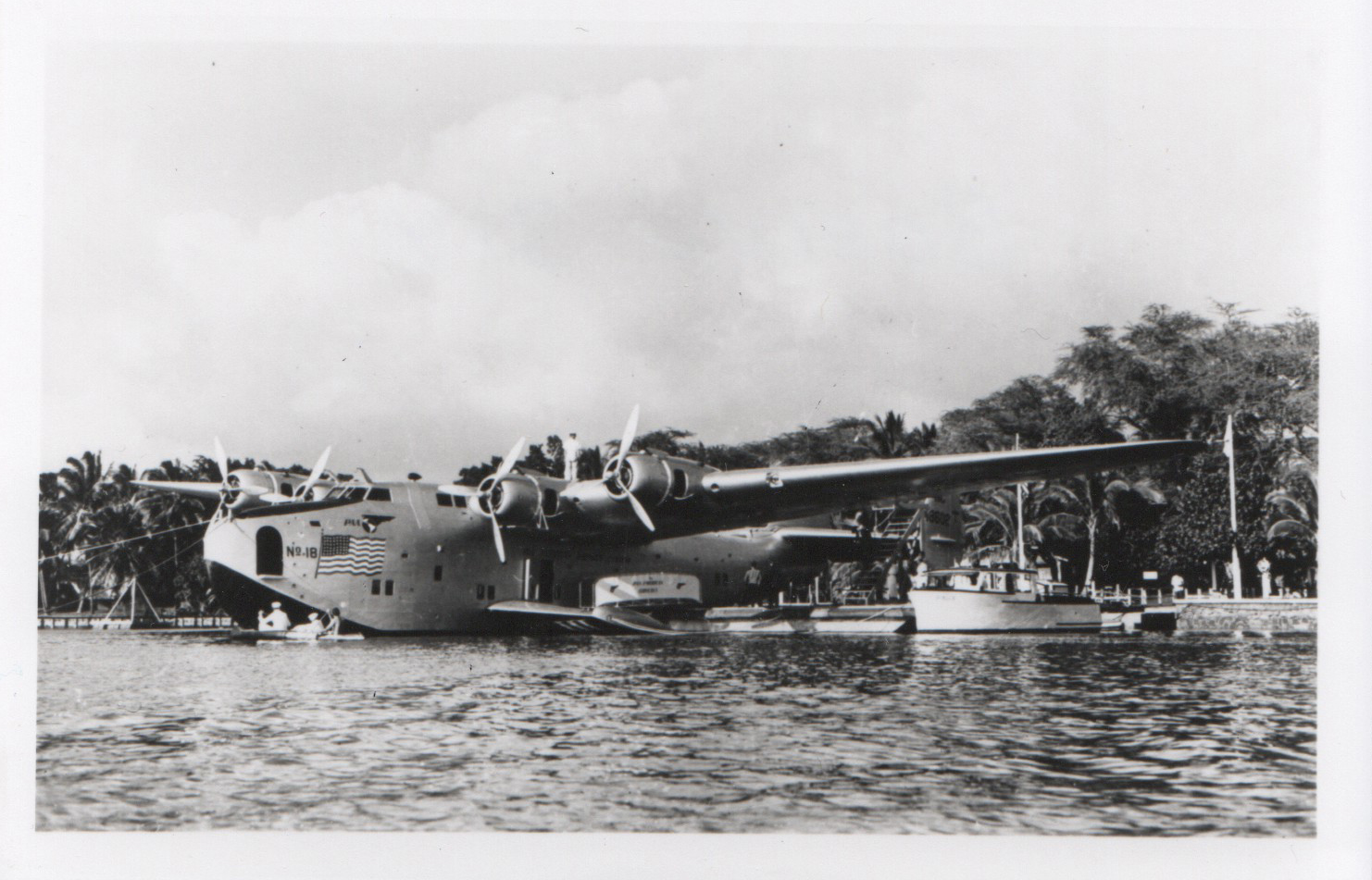

However, Mr. Eskridge was the only radio operator in the Honolulu Field Office and could not be expected to operate the station alone indefinitely. As it was, he did not leave his post for 62 hours following the attack. On December 12, he was joined by another recently hired 22-year-old FBI radioman and fellow ham radio operator, Melvin H. Barrett, who had been sent 5,000 miles from the FBI Laboratory. The last leg of Mr. Baarrett’s trip, made on a Boeing 314 Yankee Clipper “Flying Boat” with a handful of other Americans, was the first commercial flight to attempt to make the 18-hour journey from San Francisco to Honolulu since the outbreak of the war. It took courage to make that trip. No one knew for certain the whereabouts or the strength of the Japanese armed forces, which just days before had shown such fury. The Flying Boat landed in an unobstructed area of Pearl Harbor itself, and Mr. Barrett thus became one of the first persons from outside the area to view the horrific destruction. Messrs. Eskridge and Barrett worked together at the radio station for months from that point on.

Mr. Corbitt continued at his San Diego post as well but was able to obtain assistance as needed from other FBI employees. The San Diego and Honolulu also processed radio, telephone, and teletype messages to and from FBI Headquarters and Bay Station Chesapeake in Maryland. Radio messaging continued to be extremely heavy for the duration of the war.

On December 11, Germany declared war on the United States as well due to Adolph Hitler’s desire to engage America along with Japan, whom he considered a military partner.

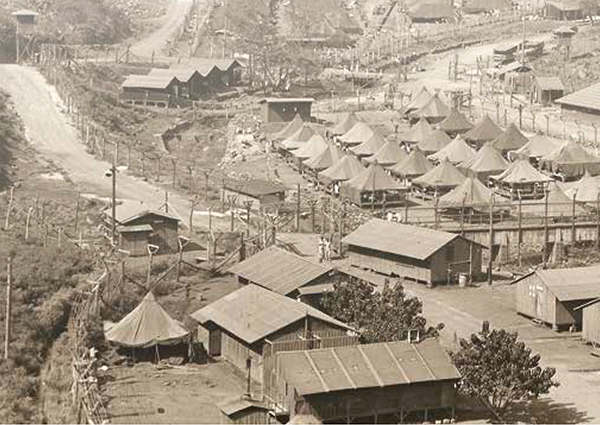

The advent of a world war put all FBI employees in Hawaii under tremendous pressure. All 16 Special Agents and 10 other personnel, in addition to Messers. Eskridge and Barrett, served not only under blackouts, curfews, and shortages, but also under constant concern of invasion by the Japanese. The threat eased only after the decisive U.S. Navy victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942 made another Japanese attack unlikely.

The FBI Goes to War

The attack by armed forced of the Empire of Japan on the United States military base at Pearl Harbor was a shock on a par with anything Americans had ever experienced. America had been attached on its own land by a strong hostile foreign power, something not experienced since the previous century.

The attack was unexpected in most quarters, but not all. Japan had made no secret of its expansionist plans in Asia and throughout the Pacific Ocean region, and the United States military was an obstacle it wanted to remove. Hawaii and Pearl Harbor had been theoretical targets by military strategists since at least the 1920’s even though the region was not well known to the public. Diplomatic talks between the United States and Japan had failed to avoid an armed conflict, and the Nation was in war. The FBI would be part of the effort, and in fact the Bureau’s investigative responsibilities already had been expanded greatly in the late 1930s regarding espionage, counterespionage, and sabotage. The Bureau was concentrating on much more than kidnappings, financial crimes, and gangsters.

An airplane similar to this Boeing 314, more commonly known as a Pan Am Clipper or Flying Boat, carried FBI radio operator Melvin Barrett and others from San Francisco on the first commercial flight to Honolulu after the attack on Pearl Harbor

In 1940, the FBI was a small entity with 896 Special Agents and 1545 other personnel with an annual budget on $8.8 million. By 1945, it had 4400 Special Agents 7400 other employees with an annual budget of $44 million. The FBI continued to grow to its present size of over 35,000 employees and an annual budget of approximately $10 billion.

The FBI’s internal communication and computer capabilities continued to grow as well, and by the 1960s and 1970s these functions began to be split off from the FBI Laboratory Division into new specialized Divisions.

The transmitters and receivers in large metal boxes with rows of glowing tubes inside from days of yesteryear had helped win a war and given rise to a new world.

What Ever Happened to the FBI’s World War II Generation of Radiomen?

All the radiomen have passed away over the eight decades since Pearl Harbor, along with most of the 15 million Americans who served in World War II.

Dwayne Eskridge later became an FBI Special Agent and spent his career in California. He was quoted as saying that “I served in the FBI from Pearl Harbor to Patty Heart and survived them both.” Coincidentally, he grew up in Arizona, which is the name of the battleship that suffered the worst fate in the bombing and is memorialized at Pearl Harbor. He died in 1993.

James Corbitt transferred back to FBI Headquarters in 1942 and continued with his career in communications with the FBI as a Radio Maintenance Technician. He retired in 1992.

Melvin Barrett became an FBI Special Agent before leaving to work at other Federal agencies in 1951. He retired in 1973 and died in 2016.

Ivan Conrad went on to become the Assistant Director, the top job, in the FBI Laboratory. He retired in 1973.

Robert Shivers left the FBI in 1944 to accept another Federal Government position. He died in 1950.

Frank Sullivan, who later managed radio communication traffic, became an FBI Special Agent in 1945. He died in 1960 while assigned to the FBI’s San Diego Field Office.

FBI Electronic Maintenance Technicians

Many FBI employees have worked in telecommunications over the decades. Women joined the ranks in the 1940s and quickly became essential due to their skills and dedication. They were vital during World War II.

Now often carrying the job title of Electronic Maintenance Technician (EMT), they are professional workers within the FBI. A sizable number of them continue with electronics in their personal lives and are active ham radio operators just like their FBI predecessors.

There is risk to telecommunications jobs, what with working in difficult conditions and often climbing towers in challenging locations. Electronic Maintenance Technician Billie Wade Taylor lost his life due to an accidental fall while working on an antenna on the roof of a six-story building in Lakeland, Florida in 1965. He is recognized along with other FBI employees who have given their lives in the performance of their duties. The communications center in the FBI’s Tampa Field Office is named in his honor.

The 1941 FBI Field Office Location in Honolulu

And what about the Dillingham Building in Honolulu, which now is known as the Dillingham Transportation Building? Although the FBI Field Office moved to other office space long ago and there is not much to indicate the FBI field office ever was located there, it still stands. The building, constructed in 1929 and named for a prominent local businessman and developer, generally looks the same as it did all those years ago. It is occupied today by other tenants.

The Dillingham Building, home of the FBI’s Honolulu Field Office in 1941, then and now

Reflection

On December 7, 1941, 2,403 Americans were killed and 1,143 were wounded. None of them were FBI personnel. During the course of World War II over the following four years, some on-duty FBI personnel and some employees who had enlisted or drafted would lose their lives in other locations. A plague with their names was displayed prominently outside the FBI Director’s office for decades in their memory.

The armed conflict in the Pacific War would be costly. Over 111,000 United States military personnel were killed or listed as missing and over 253,000 were wounded. The Japanese fared far worse. Over 1.7 million were killed or listed as missing and 94,000 were wounded.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor, initially thought to be a brilliant tactical strike by Japanese military planners, had been a horrific strategic blunder.

Books, Video, and Other Articles

Many books and video are available that mention the FBI’s activities during World War II. Images of some of the best books and videos are posted within this article.

As well, there are links to separate long articles about two of the men mentioned in this article (Dwayne Eskridge and Robert Shivers) that were written by Dr. Raymond J. Batvinis, a retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent, historian, author, teacher, and lecturer.

ERNEST JOHN PORTER

A retired Unit Chief and Supervisory Public Affairs Manager at the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington, DC, Mr. Porter worked with authors, radio shows, motion pictures, television shows, documentaries, FBI History, lecturing, and special projects for the FBI for nearly 40 years. He is the developer, owner, and manager of FBIOGRAPHY.