The 1932 Kidnapping of the Young Son of Famed Aviator Charles A. Lindbergh From His Crib Startled the World. The Investigation Lasted Over Two Years, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation Played a Role in Solving in One of the Most Famous Cases in the History of American Law Enforcement. 90 Years Later, Competing Theories Still Exist About the Crime, How It Took Place, and Who Was Involved. FBIOGRAPHY Looks at Some of What Has Been Presented, Written, and Discussed for Decades

By Jack French, with Ernest John Porter

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

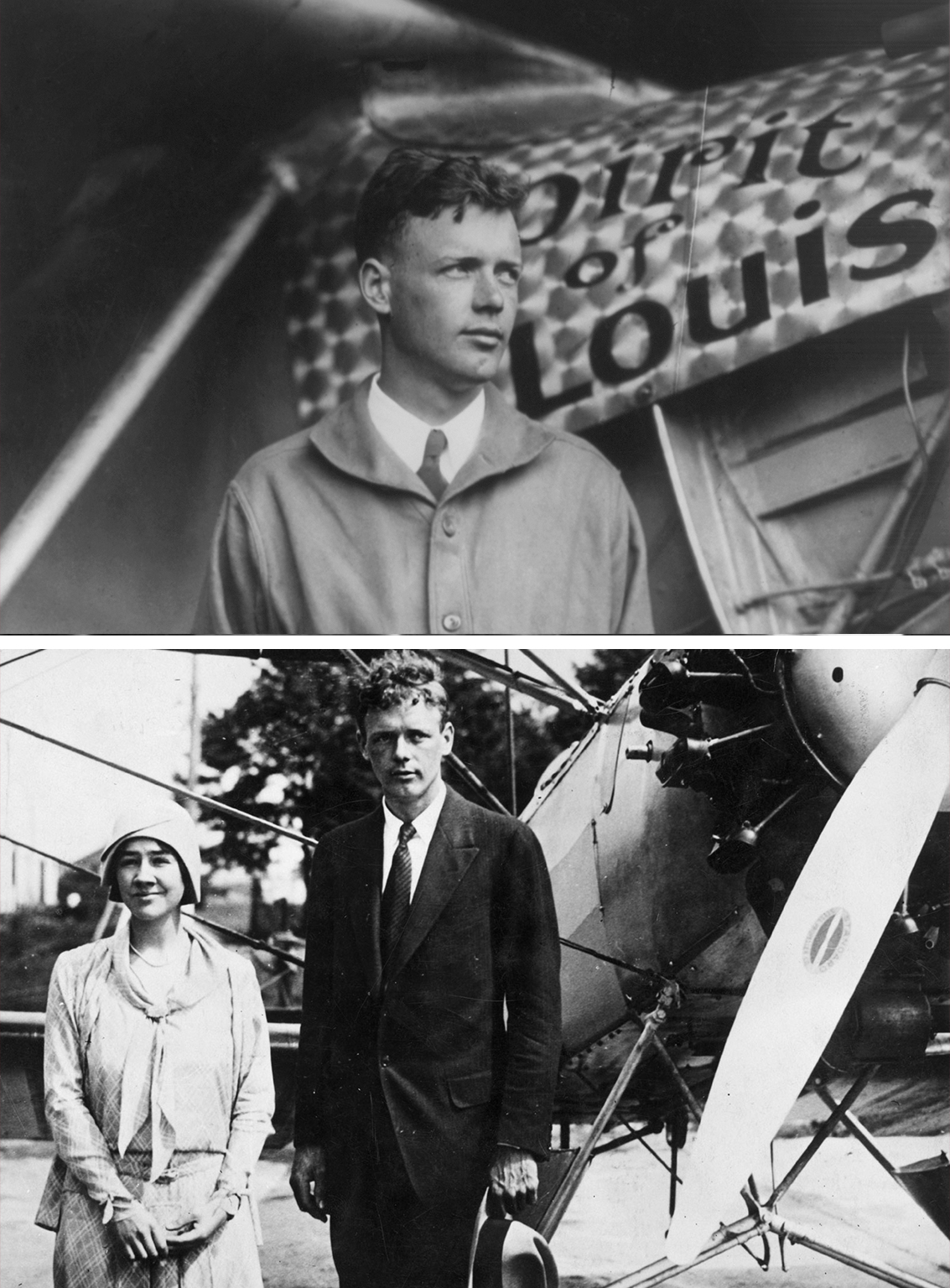

The better part of a century has passed since a 25-year-old American pilot named Charles Augustus Lindbergh first came to wide public notice. Already known to an extent in parts of the Midwest, especially around St. Louis, for barnstorming, wing walking, parachuting, and being a bold and highly capable officer in the U.S. Army Air Corp Reserve and U.S. Air Mail pilot, he was always open to new challenges in the growing but still dangerous field of aviation. He therefore became intrigued when he learned that a $25,000 aviation prize first offered in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I was still unclaimed. Known as The Orteig Prize, named after the New York hotelier Raymond Orteig who sponsored it, the money (equivalent to $375,000 in 2020) was intended to foster the advancement of aviation. It would be awarded to any pilot or pilots who first successfully flew a powered airplane nonstop from New York City to Paris, or vice versa.

By the time Lindbergh became interested, the terms of the prize had been broadened and flight technology had advanced significantly from what it was during World War I (1914-1918, then called The Great War). Competition for the prize intensified, and six pilots were killed or lost when attempting flights as other pilots continued with their plans. Lindbergh was undaunted and, after securing financing from businessmen in St. Louis and having a purpose-built airplane constructed for the flight by the Ryan Aircraft company in San Diego, California.

As has been recounted many times through the decades in newspapers, books, motion pictures, and documentaries, Lindbergh took off in the Spirit of St. Louis on May 20, 1927. He successfully made the flight mainly by compass, altimeter, a chart, and dead reckoning in 33.5 hours in very challenging conditions, including great fatigue and wing icing. News of the flight captured the attention of the world, made him an instant hero, and gave him status in aviation, great financial and business success, and even lead the bachelor to meet a refined young woman from a wealthy New Jersey family, Anne Morrow, and marry her in 1929.

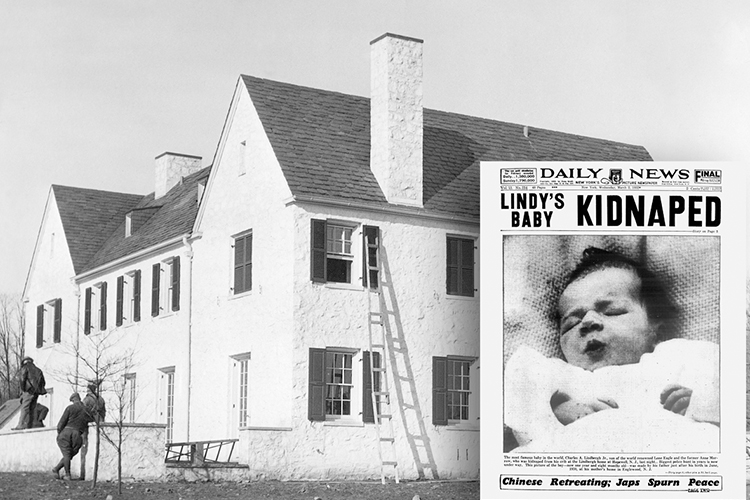

The Lindberghs welcomed their first child, Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., in 1930. To give themselves more, much-needed privacy, they had a large, 20-room new home built for them on a 400-acre site near the small community of Hopewell, New Jersey, not far from Princeton. The area was rural (yes, there are some rural areas in New Jersey), off the beaten path but not too far from roads or cities, perfect for peace and quiet and possibly also for a small airplane landing strip that Charles wanted to build for his use.

The new home still was partly under construction early in 1932, but the Lindberghs were living there with their child on weekends while staying with the Morrow family in Englewood, New Jersey during the week. They had servants with them at Hopewell, but no security, and the property was not fenced or patrolled.

The Lindberghs planned to settle into a new life of comfort, style, business, family, friends, culture, and travel. Anne was pregnant with their second child, another son who would be born the following August. But the world they knew was about to cruelly and unexpectedly turn against them. In the aftermath, it would shake them to their core. It also would impact the Nation, Congress, the world, public opinion, legislation and law enforcement, particularly the New Jersey State Police, the New York City Police Department, the United States Department of the Treasury, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

INFORMATION RELATED TO THE CASE

There are photographs and footage related to the Lindbergh Kidnapping, much of which can be found in the books, motion pictures, and documentaries that are contained in the pages that follow.

This Internet address will take you to an exhibit by the New Jersey State Police Memorial Association. Follow the main page to the Museum section on the right side, then scroll down to Lindbergh.

The FBI’s main website contains an article and photographs about the Lindbergh Kidnapping:

The official collection of the FBI’s investigative reports on the case is maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration at its facility located in College Park, Maryland. There are many thousands of pages. As well, some of the reports may be found online through search engines.

THE INVESTIGATION

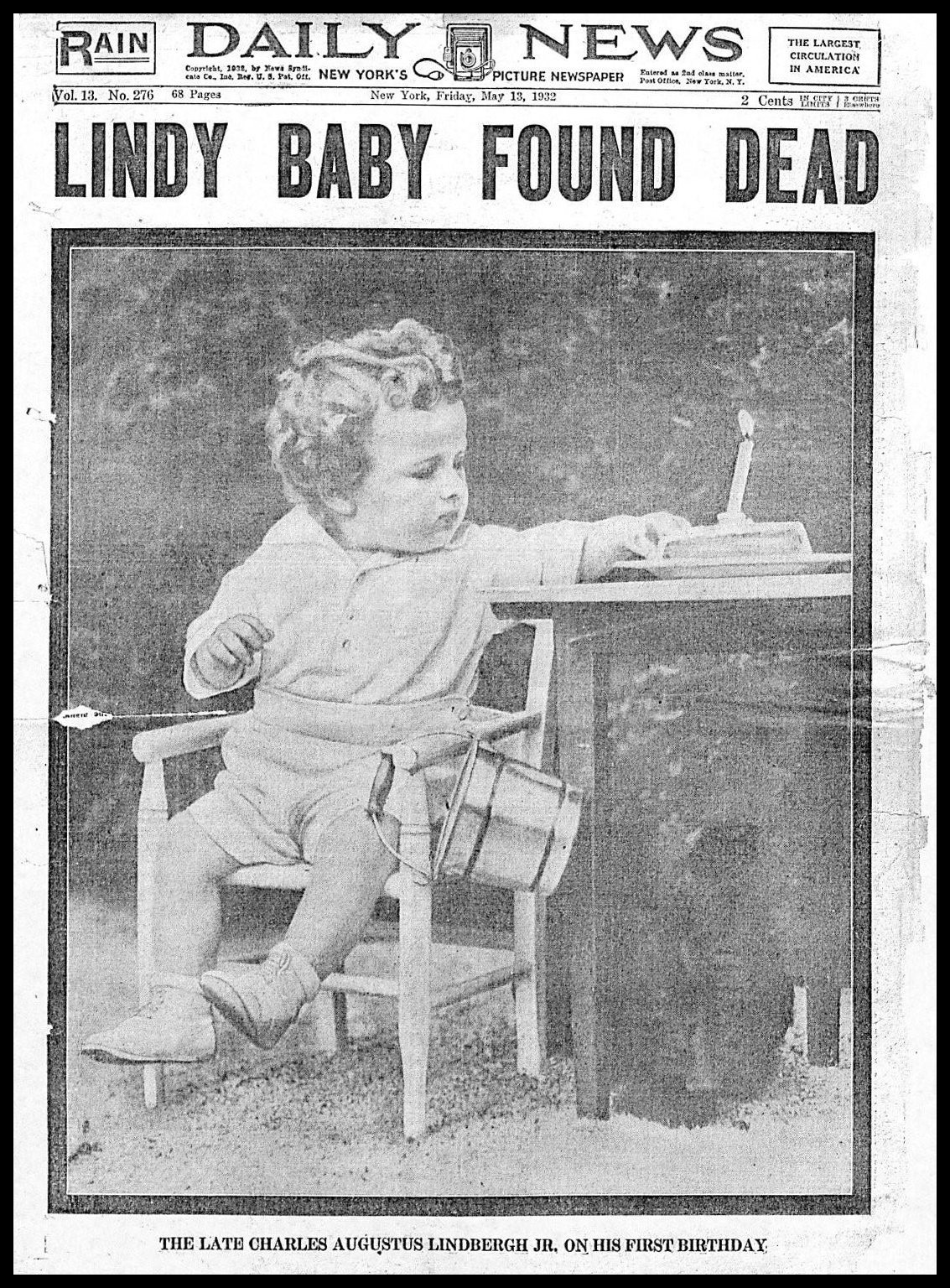

Once the baby’s death was confirmed, the thrust of the investigation of the law enforcement changed from searching for the victim to catching the killer(s). The theories of who was responsible varied greatly in the minds of law agencies, as well as the media. Most believed it was the work of a criminal gang. A few of the tabloids suspected that Lindbergh accidentally killed his own son and then faked the kidnapping. Another weird theory was that Lindbergh’s sister-in-law, in a jealous rage, threw the baby out the window and let Lindbergh conceal it with a bogus kidnapping. The most outrageous suggestion was that the Japanese staged the kidnapping and murder to cover up the bad publicity they were getting regarding their brutal takeover of Manchuria. No one suspected it might be a lone German immigrant in the Bronx, not until a New York psychiatrist constructed one of history’s earliest criminal profiles indicating that conclusion.

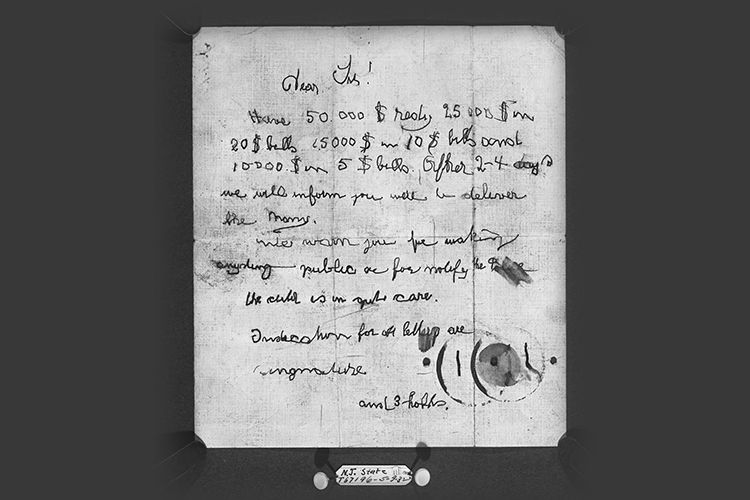

Dr. Dudley Shoenfeld in November 1932 delivered to authorities a profile of the kidnapper, based upon his examination of all the evidence including the numerous ransom notes. He stated that no gang was involved; it was all work of one man…a recent German immigrant who had been institutionalized, was an unemployed carpenter, about 33-36 years of age, was tyrannical, supremely confident, lived in the Bronx, and when arrested, would never cooperate with police. FBI Agent Leon Turrou worked closely with the New Jersey authorities. In Manhattan, three men headed-up the investigative effort: Detective James Finn, an NYPD 27-year veteran; FBI Agent Thomas Sisk; and Lt. Arthur Keaten of New Jersey State Police (NJSP). J. Edgar Hoover had been designated by President Herbert Hoover (no relation) to coordinate the federal response. But with no federal violation or jurisdiction, the FBI could only act in support of the NJSP.

Most of the law enforcement work concentrated on identifying the killer by tracing the ransom money, an arduous process. When a ransom bill was found by a bank, the authorities went to the depositor, usually a NYC business, to find out what could be recalled about who passed it. In view of the time lapse, virtually no one remembered the bill or the passer. But identifying the bills by serial number got a little easier when President Roosevelt, by executive order, directed all persons with gold certificates to turn them in before May 1, 1933. On that last day, the kidnapper, using the alias of “J. J. Faulkner” and an incomplete address, went to a NYC bank and exchanged $ 2,980 in gold certificates (all part of ransom) for ordinary greenbacks. The follow-up investigation on that incident was unproductive.

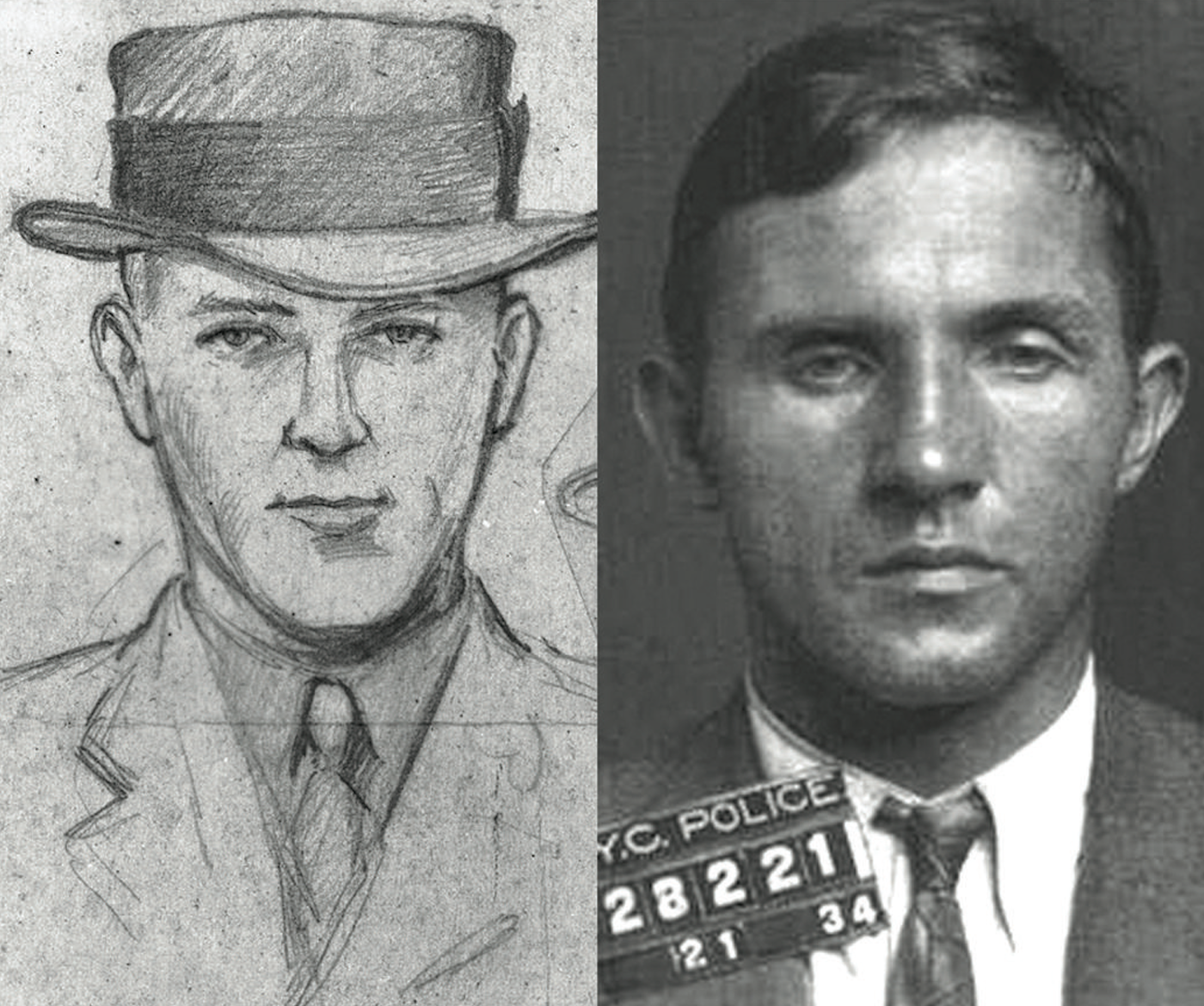

In early 1933, Schwarzkopf enlisted the help of Arthur Koehler, the wood expert of North American, and turned the ladder over to him. Koehler spent months searching for the source of the wood used in it, ultimately tracing most of it from an origin mill in South Carolina to a retail lumber yard on White Plains Avenue in the Bronx. But the latter kept no cash sales records so the trail ended there. As 1933 turned into 1934, leads were drying up and media interest was fading. But the ransom notes kept appearing in deposits and banks routinely notified the authorities. By now gold bills were more scarce and people who accepted them remembered more about the bill passer. Their descriptions were always the same: lone white male, mid-30s, average height and weight, German accent, snap brim hat. Unfortunately, that description fit untold hundreds in the Bronx.

THE SOLUTION

Finally, on September 18, 1934, after two and a half years of exhaustive work coupled with bitter frustration, the big break came. A $10 gold certificate from the ransom money was deposited by a gas station at Lexington and 127th Street in upper Manhattan. On its margin was written “4U 13 41 N.Y.”, obviously a New York auto license number. At the gas station, Detective Finn, Special Agent Sisk, and Lt. Keaten learned from an attendant, James Lyon, that he had accepted the bill from a customer driving a 1930 Dodge. Lyon feared the bill might be counterfeit so he wrote the customer’s New York license number down before he could drive away.

That license number was registered to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a 34-year- old German carpenter living at 1279 East 222nd Street in the Bronx. This house was only 10 blocks from the White Plains lumber yard and one mile from the park where Condon and the kidnapper negotiated, as well as less than four miles from the cemetery where the ransom was paid. Hauptmann’s house was placed under surveillance by nine officers, including Finn, Sisk, and Keaten.

When Hauptmann drove away from his house the next morning, he was followed and, shortly after, arrested in his car, and searched. A $20 gold certificate from the ransom money was found in his wallet and Hauptmann admitted he had more at home. He was taken back to his home, where he lived with his wife and infant son, a five- room second story flat he rented, along with a separate garage, which he had built. In an intensive search of the garage, authorities found $1,830 secreted in one area and $11,930 hidden in another section, every bill part of the ransom money. His toolbox was missing one chisel, the same as the one found at the kidnap site. The “Crime of the Century” investigation had just taken a giant step forward.

Hauptmann was questioned repeatedly in custody of New York authorities. Dr. Condon was brought in to identity him in a line-up and FBI Special Agent Turrou accompanied Condon. J. Edgar Hoover came to the police station and briefly interviewed Hauptmann. The prisoner denied any participation in the kidnapping or murder of the baby; he claimed the ransom money found at his domicile was given to him by a friend, Isidor Fisch. Handwriting samples were taken from Hauptmann and rushed to the FBI Crime Laboratory. FBI handwriting examiner Charles Appel, Jr. soon notified Special Agent Turrou that the writings were a match. The FBI officially withdrew from the case on October 10, 1934 as prosecution would go forward in New Jersey state court.

THE TRIAL

The county courthouse in tiny Flemington, New Jersey was the scene of the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, and it began on January 3, 1935. It would last six tumultuous weeks during which hundreds of spectators arrived; some were unknown, many others were famous personalities. The only hotel in this small town had 50 rooms and received requests from over 900 people. Radio, magazine, and newspaper representatives flooded the town, encompassing about 300 reporters. These included prominent authors and journalists: Edna Ferber, Fannie Hurst, Walter Winchell, Damon Runyon, Kathleen Norris, and Alexander Woollcott.

Thomas Trenchard was the preceding judge and swore in the jury of four women and eight men. The Attorney General of New Jersey, David T. Wilentz, headed up the prosecution while the defense was led by a flamboyant attorney from Brooklyn, Edward J. Reilly. Curiously, this was Wilentz’s first criminal case in court, while Reilly had defended hundreds of accused murderers. Paying for Hauptmann’s legal team caused a bidding war among various media venues; the New York Evening Journal, part of the Hearst syndicate, topped the other offers and thus achieved exclusive access rights to Hauptmann.

The prosecution’s case was powerful. They put on the stand over 40 witnesses and introduced over 300 pieces of evidence. It was established that Hauptmann was in prison in Germany for a series of robberies and paroled after four years. Upon release, he was arrested again for theft but escaped from jail. As a fugitive, he tried three times to enter the USA illegally before he finally succeeded. Eventually he became a carpenter, got married, and settled in the Bronx. He never worked a day after the 1932 ransom payment but lived a lavish lifestyle. He had nearly $ 15,000 in hidden cash when arrested in 1934, all bills part of the ransom.

Handwriting experts determined that his matched all of the 15 ransom notes in style, mis-spellings, and structure. Condon identified him as the man he negotiated with and to whom he ultimately turned over the $ 50,000. The ladder left at the scene was a home-made, collapsible one, made by a carpenter; it contained wood from a lumber yard frequented by Hauptmann and one piece of it was taken from his attic floor. Condon’s telephone number was written on the door frame of Hauptmann’s closet.

After 17 days of prosecution testimony, the defense opened on January 24 with Hauptmann in the witness chair. His defense was simple…he was completely innocent. He did not kidnap the baby, he did not kill the baby, he wrote none of the ransom notes, he did not get the ransom payoff and his wife was his primary alibi. All the ransom money found in his garage was unknowingly accepted by him, given by an acquaintance, Isidor Fisch, who subsequently had died of tuberculosis in Germany in March 1934. The trial ended on February 13, 1935. The jury deliberated for 11 hours and 14 minutes and returned a verdict of guilty of murder in commission of felony burglary. Subsequently, Hauptmann was sentenced to death. After a lengthy appellate process, the New Jersey Supreme Court affirmed the conviction on October 9, 1935. The case was further appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court who declined to review it on December 9, 1935. While on death row in the state prison in Trenton, Hauptmann was visited by the NJ governor, Harold Hoffman, who offered him life imprisonment instead of execution if Hauptmann would only confess. He refused. The Hearst Syndicate offered $ 100,000 to be given to Hauptmann’s wife if he would confess to them. He also refused that offer. On April 3, 1936 Hauptmann died in the electric chair. It was exactly four years and one day from the date of the ransom payoff; it is unknown if Hauptmann was aware of this irony.

While nearly all of the evidence pointed to Hauptmann as the lone perpetrator, it was never firmly established that he was alone in this crime. Some reasonable people thought he may have had some assistance in this matter, including possibly someone in Lindbergh’s household staff. Others thought that Hauptmann’s supposed cunning actually represented the planning of a more intelligent co-conspirator who was never identified. This historic kidnapping and murder in some ways is akin to the assassination of a U. S. president, which is virtually always the act of a lone, white, male sociopath. But for many, an attack on the most protected man in America by one previously unknown person was simply not possible. They believed instead it must have been the work of some diabolical group. So as in the case of JFK’s assassination, they view Lee Harvey Oswald as just the point man for a cabal of Cubans or the Mafia, or even some secret Federal agency.

AFTERMATH

The strong interest and boundless publicity about this case did not diminish with the death of Hauptmann. In many respects, they only increased. German-affiliated groups in this country made it clear that not only was Hauptmann not guilty of anything, but his conviction was solely the result of prejudice against Germans because of the residual hatred from The Great War (World War I.) Magazines and newspaper articles not only doubted Hauptmann’s guilt, but postulated that the baby’s corpse was not Lindbergh’s son. Ellis Parker, a prominent detective in the 1930s, claimed the kidnapper was actually Paul Wendel, a former mental patient. Any newspaper could sell out an edition just by putting Lindbergh in a headline. To escape the barrage of publicity hounds who besieged them constantly, the Lindberghs, with their second infant son who was born in August 1932, had relocated to England in December 1935. Their departure did not quell the publicity in any way.

Bogus and fanciful theories found their way into all the media and entertainment venues. Consideration was given to putting members of the Lindbergh jury on the vaudeville circuit. Gift shops sold pictures of the baby victim and marketed miniature replicas of the ladder used by the kidnapper. And if the corpse found was not Lindbergh’s son, he must have grown into a man, so three pretenders arose, all making that claim: Robert Dolfen, Harold Olson, and Kenneth Kerwin. Each one of this fake trio garnered media publicity with their claims and enjoyed the spotlight.

But the greatest initiator of media ink proclaiming Hauptmann’s pristine innocence was his wife Anna. Absolutely convinced he did nothing wrong, she devoted all her time from his death to hers, in a fervent effort at his redemption. She lived to be 96, dying in 1994, and spoke to a multitude of groups and was interviewed by countless reporters and journalists in those six decades. While her legal arguments were rejected by all the courts in which she had her lawyers file civil suits, she was quite successful in converting many media representatives into ignoring all the evidence and declaring her husband’s innocence. Anna even convinced some successful authors, including Anthony Scaduto and Ludovic Kennedy, each of whom wrote and published a large volume rejecting all the evidence and anointing Hauptmann the real victim.

Charles and Anne Lindbergh never got over the loss of their firstborn son. However, they had more children and went on with their lives, which turned out to be as unpredictable and remarkable as their first years together. The 1998 book entitled Lindbergh by A. Scott Berg is an outstanding reference.

The remains of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. were cremated and scattered during a private flight by his father over the Atlantic Ocean. The body of Bruno Richard Hauptmann was cremated shortly after his execution. Charles Augustus Lindbergh lived until 1974. He was age 72, and was buried in Hawaii at his request. Anne Morrow Lindbergh lived until 2001 and died at the age of 94. Her body was cremated and her ashes were scattered over various places in Hawaii.

PART TWO: SIGNIFICANT BOOKS AND THEORIES ABOUT THE CASE

Kidnap: The Story of the Lindbergh Case by George Waller (Dial Press, 1961)

While many books about the crime of the century preceded it, Waller’s book was by far, the most detailed and thorough examination of the crime and the resulting trial, of all publications up to that point. Reviewing the book for the University of Minnesota Law Review, William L. Prosser accurately stated:

“Waller, a free-lance writer and former magazine and newspaper editor, who was a student of journalism at near-by Temple University at the time of the case, has retold the story in considerable detail, and with an unbiased accuracy which has been sadly lacking in some previous accounts.”

After its American debut, it was published in Germany in 1963 under the title: Der Fall Lindbergh Das Verbrechen. The American edition is massive, just under 600 pages, and it contains 27 period photographs. Waller assumes his readers were well aware of the background and enormous fame of Charles Lindbergh so the very first page has his description of the kidnapping. He reveals in pains-taking detail everything about the Lindbergh estate home and the people within it on March 1, 1932 when a home-made ladder was placed against the residence and the kidnapper climbed up to the nursery window.

Waller makes no secret about the strong influence that Lindbergh utilized from the very beginning in terms of the investigation. Relatives of kidnapped victims usually have no say-so in terms of what the authorities do in order to solve the case and return the victim unharmed to the family. But Colonel Lindbergh, with no experience in crime solving, insisted on dictating terms and parameters to local and federal officials handling this case. Sometimes he was successful, but fortunately in the matter of recording the serial numbers of the ransom cash, his views were rejected. Lindbergh forbade any recording of the serial numbers as the first kidnap note demanded, but he was overruled. Had a record not been made of those serial numbers, the case never would have been solved.

The role of Dr. John Condon, who successfully maneuvered himself into being the go-between for the ransom payoff to the kidnapper, is detailed very well by Waller, setting forth every communique between Condon and the kidnapper. Their personal meetings were devoid of police surveillance at Lindbergh’s insistence. Nor does Waller ignore the more sordid aspects of the crime after the decomposed body of the tiny victim is discovered; an intruder broke into the morgue, photographed the little corpse, and then sold copies of the picture.

Efforts of two men, neither of whom was in law enforcement, which almost resulted in the solution of the case, are set forth. Dr. Dudley D. Shoenfeld, an experienced psychiatrist at Mt. Sinai Hospital, was allowed to examine all the ransom notes and other evidence collected. After months of study, he prepared a criminal profile of the kidnapper that proved to be amazingly accurate, although his insightful conclusions were not confirmed until Hauptmann was arrested.

Arthur Koehler of Wisconsin, the “Sherlock Holmes of wood,” spent months examining the home-made ladder of the kidnapper. With a microscope, he detected that a defective blade at a saw mill had produced a particular mark in some of the boards. He eventually located that saw mill in McCormick, SC and through more investigation, traced their shipment to a Bronx lumber yard. But it was another dead-end; the sale of that batch of those boards was unrecorded at the lumber yard.

One half of Waller’s book recounts the crime, the investigation, and Hauptmann’s capture. The second half is devoted to the trial and the lengthy appeal process. All the highlights of the testimony of both the prosecution and the defense as well as the introduction of physical evidence are covered with objectivity. Portions of the testimony are included, repeating verbatim statements from actual transcripts of the trial, but only to reinforce critical facts. At the book’s conclusion, he takes no position on the guilt of Hauptmann but merely lets the mountain of evidence stand in mute confirmation.

The only fault in this book, which keeps it from being a convenient reference book, is that it contains no index.

Scapegoat by Anthony Scaduto (Putnam’s, 1976)

This book is sub-titled “The Lonesome Death of Bruno Richard Hauptmann” and to amplify the author’s intent, the publisher added in all caps on the front dust jacket “Hauptmann was innocent, his conviction for the Lindbergh baby kidnapping, a frame-up.“

Most people know that the term “scapegoat” originates in the Bible where a goat was sent into the wilderness after the Jewish chief priest had symbolically laid the sins of the people upon it. In the modern era, it applies to a person who is blamed for the wrongdoings or sins of others, especially for reasons of expediency.

In the initial pages of this book, Scaduto self-describes himself as “the so-called Mafia expert for the New York Post” who possesses “a hostility toward the guardians of peace and tranquility” so he “questioned the morality and integrity of many policemen and prosecutors.” This puts him in position to doubt all the prosecution’s testimony against Hauptmann and regard all their evidence as tainted. And he does so in the next 500 pages.

Scaduto begins his tale with a letter he received in 1973 from an ex-con, “Murray” who had been involved with the New York “mafiosa.” The letter said that Hauptmann was innocent and Murray could prove it. This sparked a three-year investigation by the author. Murray does not appear in the book again until page 71, when Scaduto, armed with tape recorder, begins to interview him. Murray’s story is that while Hauptmann was on death row, Ellis Parker made Murray a deputy so he could take custody of Paul H. Wendell. Parker insisted that Wendel, a former mental patient, was the real Lindbergh kidnapper and he would confess if pressured.

After five days in Murray’s custody, Wendel confessed he kidnapped the baby, he wrote all the ransom notes, he got the $ 50,000 payoff, but the baby, whom his family was keeping, fell out of crib and died. Wendel took the body back to Hopewell vicinity and buried it in a shallow grave. Later, he did not want to be found in possession of the ransom money, so he turned it over to Isidor Fisch, who in turn, gave it to Hauptmann. Murray claimed Wendel later recanted but Parker took his confession to Attorney General Wilentz, who refused to take action on it. Despite featuring the death of the baby in Wendel’s testimony, Scaduto alternatively claims the baby found was not Lindbergh’s and that his son grew to adulthood with another family. One possibility was Harold Olson, who claimed to be the Lindbergh baby. Scaduto at first avoids an interview with Olson, because of fear that “he’d turn out to be some kind of “nut.“ But the author later goes on to interview Olson and finds his tale convincing.

Virtually every page in the book consists entirely of dialogue, in effect resembling a conversational novel. Long interviews of various sources, as well as about a hundred pages of trial transcript appear. The latter is chiefly all Hauptmann’s denials from the stand. Scaduto saved his most significant interviews for the last pages. For two days he interviewed Anna Hauptmann (then 76 years old) beginning on page 425 and he confronted Attorney General Wilentz, starting on page 476. As one might expect, Anna insists her husband was innocent while Wilentz believes he was guilty. Scaduto has not mentioned his tape reorder since the contact with Murray, so the reader does not know if the volume of conversation set forth throughout the book are transcripts from tape or merely Scaduto’s recollection. But in his End Notes, the author admits neither Anna nor Wilentz were actually recorded, but he “reconstructed” their statements shortly after.

The Airman and the Carpenter by Ludovic Kennedy (Wm. Collins & Son, 1985)

In 1982 the author listened to Anna Hauptmann on television and he concluded her husband was innocent of all charges. Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy (knighted in 1994) a Scottish author, journalist and broadcaster had a reputation in the British Isles as a “glorious anti-establishment” crusader who had devoted his career to exposing miscarriages of justice. Hearing Anna’s story inspired him to take on another quest. His efforts resulted in a BBC documentary, this 438-page book, and a 1996 HBO movie, Crime of the Century.

Kennedy spent several months in the United States, touring all the sites of the Lindbergh kidnapping, interviewing all surviving principals, and reviewing all records he could find. He concluded, as Anna had argued, that Hauptmann was convicted only because of prejudice against Germans. In an aside to his readers, Kennedy affirms that prejudice is so strong in people and the desire for scapegoats is universal so people are blinded. Accordingly, most of his book contends that all the prosecution witnesses, including law enforcement officers, lied on the stand and fabricated the evidence.

Some of the best parts of his book were not written by him, but by Anne Lindbergh, an equally talented writer. She gave Kennedy complete access to her diaries and letters written in the 1930’s and he quotes from them liberally. They are detailed, personal, and poignant, revealing all her deep feelings as she and her husband raised their first son, only to have him snatched from his crib and killed. Her suffering and later painful recovery when their second son is born are set forth in loving terms.

The book is lavishly illustrated with 57 different photographs, some not published since the Great Depression. Kennedy portrays the Lindbergh and the Hauptmann couples in very similar terms: young, loving, kind, responsible, and good citizens. But all of the law enforcement agencies are criticized as untruthful and close-minded. He maintains that most police, when first finding a suspect, thereafter ignore all contrary facts and instead look only for collaborative evidence, which if they cannot find any, they manufacture it. In his analysis, this dominated the Lindbergh investigation and trial.

Kennedy uses some sections of the trial transcripts in his book, but concentrates on the two closing summaries of the defense and the prosecution and he quotes substantial portions of both. He emphasizes that defense attorney, Edward J. Reilly, “laid bare the essential weaknesses of prosecution’s case” while Kennedy damns David Wilentz’s summary as “one of the most distasteful on record.” Kennedy closes his book with a facsimile of a cordial letter he received from Anna Hauptmann in response to his Christmas card to her. This is followed by the entire text of the December 27, 1935 letter Hauptmann penned to his mother, explaining his total and complete innocence.

So who did kidnap and murder the Lindbergh baby if it wasn’t Hauptmann? In the initial pages of his volume, Kennedy explains that he cannot name the actual killers; that was not the object of his investigation. But he then reverses course and quickly reveals several of his suspects: an unnamed Austrian friend of Isidor Fisch; some unnamed Italians overheard in a phone call by John Condon; Fisch’s shady partners (Charles Schleser and Joe DeGrasi); a Chicago prisoner named Spitz; and an unidentified lookout seen at Woodlawn Cemetery.

The Lindbergh Case by Jim Fisher (1987, Rutgers University Press)

A former FBI Agent, Fisher has a keen eye for distinguishing truth from falsehood, plus the reliable insight of an dedicated investigator. He brought all this to his book, which examines the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. He is not only the first author with actual law enforcement experience to address this famous case, but also the first one to review all of the case archives, including some 200,000 documents, in possession of the New Jersey State Police, which had finally been completely catalogued and indexed by that agency. The result is a powerful narrative of all the factors in this case.

Fisher begins with detailing every known fact about the actual kidnapping on the evening of March 1, 1932 in terms of the discovery of the abduction, the clues left behind including the ladder and the first ransom note, the immediate response of law enforcement, and the hordes of media that appeared. He carefully lists all the proper procedures followed by law enforcement but does not shy away from noting their miscues. He also makes clear the major influence that Col. Lindbergh had over the investigation, frequently to the detriment of law enforcement’s progress.

The book traces clearly the elements of the negotiation of the ransom payoff, with the communication process involving several more random notes, personal ads in the paper to the kidnapper, and occasional untraced telephone calls. We learn the exact sequence of the makeup of the “ransom box” and the large number of gold certificates in the $ 50,000 cash bundle, turned over by Dr. John Condon. In exchange, the kidnapper sends Lindbergh on a wild-goose chase to a non-existent boat near Elizabeth Island where the infant was supposedly being held. It’s all a cruel ruse as the partially decomposed body of the Lindbergh baby is found in a woods near the Lindbergh estate a few weeks later.

The next two and a half years are rife with frustration as the ransom cash trickled into banks on a regular basis. While the serial numbers on the bills are eventually noted by the bank employees, the police and federal agents contacting the businesses who originally accepted the cash (mostly in the Bronx) are unable to identify the passer, except in the most general terms. As of September 1934 the kidnapper was still unknown and at large, but Fisher promises “It was just a matter of time before the kidnapper made a mistake that would lead to his arrest.”

On page 184 Fisher relates the details regarding the NY license number of the kidnapper’s car, which was scrawled on a $ 10 ransom bill cashed at a Manhattan gas station, which led to the arrest of Bruno Hauptmann, an unemployed German carpenter in the Bronx. A search of his garage disclosed nearly $ 15,000, all part of the original ransom. Investigating Hauptmann quickly uncovers a great deal of evidence linking him to the crime. From the arrest to the trial in January 1935, more Hauptmann connections to the kidnapping are unveiled and more witnesses are found.

The book covers the lengthy trial in all areas, including the intense media coverage, the strategy of both the prosecution and defense, and the parade of several witnesses on both sides. Fisher provides personal details by selecting pertinent pages of the transcript for inclusion. His selection of specific illustrations is fascinating, including Anna Hauptmann’s passport, Hauptmann’s handwriting samples, the reward poster listing all the serial numbers of the ransom bills, and even the first page of Hauptmann’s “autobiography” serialized in the New York Daily Mirror.

Fisher completes his book with the somber ending of Hauptmann’s life in the electric chair on April 3,1936 following months of appellate reviews and stays of execution. He then thoughtfully adds 30-page of notes, explaining in greater detail pertinent material relating to each chapter, and lastly, a helpful index to this 480-page book.

The Ghosts of Hopewell by Jim Fisher (Southern Illinois University Press, 1999)

“Setting the Record Straight in the Lindbergh Case” is the sub-title of Fisher’s book and he sets the tone in beginning his book with a pertinent quotation by Joel Achenbach, who warns us:

“Nothing is as strong in human beings as the craving to believe in something that is obviously wrong.”

The kidnap-murder of the Lindbergh baby in 1932 was successively solved and Bruno Hauptmann was convicted on a preponderance of evidence, and after a lengthy appellate process, was executed in 1936. There was little disbelief about the solution of that case until the 1970s when revisionists challenged the trial results, many claiming Hauptmann was completely innocent, some postulating he had others assisting him, and a few arguing that the Lindbergh baby was never killed and as a grown man, he was still alive.

Various articles, books, television shows, a play, and a motion picture all depicted Hauptmann as a victim of a deliberate and overwhelming frame-up, engineered by law enforcement and the prosecution. Variations on this theme contended that the baby’s parents had accidentally killed their infant son and then created an elaborate hoax to conceal their evil deed and frame an innocent German carpenter. Still others discounted all the evidence and argued that Hauptmann was arrested and convicted only because of U.S. prejudice against Germans.

Much of the outcry that Hauptmann was innocent emanated from his widow, Anna, who with a cooperative attorney, Robert S. Bryan, filed numerous lawsuits challenging the results of the trail and seeking $ 100 million in reparations. All of their suits were eventually dismissed, and none prevailed. But her unceasing efforts continued; she did not die until 1994, when she was 96 years old. She even convinced successful authors including Anthony Scaduto and Ludovic Kennedy, who wrote popular books preaching the innocence of Hauptmann.

Former FBI Special Agent Jim Fisher carefully re-examines all the hard evidence uncovered in the original investigation and presented at the trial: all the ransom notes, the ladder used in the kidnapping, the ransom money hidden in Hauptmann’s possession, and all the other pertinent evidence. In 200 fact-laden pages, he critically analyzes all of the factual material and thoroughly debunks the various and sundry revisionist theories that surfaced in the media.

In his chapter entitled “How Many Conspirators Does It Take to Steal a Baby?” Fisher deals with the phenomenon that in situations where an assassinated victim is famous and powerful, the public at large finds it difficult to believe the act was committed by a lone sociopath. They therefore conjure up alternate theories that it must have been done by some devious but unknown organization. So, when an illegal alien with a homemade ladder and a crudely written ransom note snatched America’s most famous baby, there had to be an entirely different explanation. But anyone reading Fisher’s solid examination of all the evidence will be convinced that only Hauptmann kidnapped and killed the baby and he did it solely for the ransom money.

The Cases That Haunt Us by John Douglas & Mark Olshaker (Scribner, 2000)

The concept of this book is both unusual and fascinating. John Douglas, an FBI criminal profiler, and Mark Olshaker, a novelist and filmmaker, combine their experience and insight into a modern examination of history’s most famous crimes. They chose the most complex and sensational cases and generally devoted one chapter to each case. In their 352-page book, the following are covered: Jack the Ripper, Lizzie Borden, The Zodiac Killer, and JonBenet Ramsey Murder. One fifth of the book contains their analysis of the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby.

After relating all the pertinent facts of the crime, the investigation, and the trial, some conclusions are drawn: the ransom writer was non-American and non-English; the crime was too unprofessional to be the work of an organized gang; and the suicide of Violet Sharpe (the maid of Lindbergh’s in-laws) was caused by something more than being overwrought by police questioning. When arrested, Hauptmann was in possession of the one third portion remaining of the $ 50,000. The authors note that it is hard to believe that if Isidor Fisch really gave all that money to Hauptmann in a shoe box that Hauptmann never noticed until the box got wet from a water leak.

To believe Hauptmann was innocent requires that one believes he was the victim of the most incredible bad luck in the annals of criminal justice. A mountain of evidence pointing directly to Hauptmann: the ladder, the handwriting, his criminal background in Germany, the design of the box holding the ransom, his residence being in close proximity to all of the major sites the kidnapper appeared, Dr. Condon’s phone number written in his closet, and Hauptmann having bought a keg of nails from the same batch used in the kidnap ladder.

The book explains some of the problems with the case. Hauptmann perhaps did not get a fair trial, but that does not mean he was innocent. The investigation never ruled out someone else helping Hauptmann in the kidnapping

and some of the facts indicate he was not entirely alone in this enterprise. For example, the kidnapping was conducted on a night when the Lindberghs were supposed to be gone but plans were changed at the last minute. Could Hauptmann have been tipped off by a staff member of the Lindbergh household? In addition, Fisch did not meet the physical description of “Cemetery John”, which meant John had to be Hauptmann or a second man was involved. The author’s conclusion: Hauptmann was definitely involved in the kidnapping, but was not alone in the crime, and was not necessarily the ringleader.

The greatest overall mistake made by investigators in this entire case, the authors state, was allowing Col. Lindbergh to dictate limitations on law enforcement. In every kidnapping, the major risk for the perpetrator is obtaining the ransom package. Lindbergh refused the request of the investigators to discreetly surveil the ransom drop. They complied. Had the police covered the money drop, the chances are very great they would have grabbed Cemetery John and the case would have been solved two and a half years earlier. It wouldn’t have saved the baby, who was already dead, but it would have proved the solution to the crime.

In conclusion, the authors believe that better work by law enforcement, including being more proactive in questioning Lindbergh’s staff, as well as other strategies in dealing with Dr. John Condon, would have resulted in a clearer final solution to what they term “a classic American tragedy.”

Their Fifteen Minutes : Biographical Sketches of the Lindbergh Case by Mark W. Falzini (self-published through iUniverse, 2008)

The author of this 203-page, softcover book comes by his extensive knowledge of this famous case primarily through his employment. Fresh out of college in 1992, Mr. Falzini was hired by the New Jersey State Police to work in the archives of their museum. That institution has over 250,000 documents, photos, and evidentiary items regarding the Lindbergh case of kidnapping and murder. After 16 years in this engaging job, which he still holds in 2020, Mr. Falzini decided to write a book which would put a spotlight on the major figures involved in the investigation and trial, thus giving them their “Fifteen Minutes of Fame.”

In his preface, Mr. Falzini explains his reasoning for the exclusion of some major figures (the Lindberghs, the Hauptmanns, lead defense attorney Edward Reilly, and NYPD detective James Finn.) Justifiably, the two couples have been written about extensively in books and other print venues. However, excluding Reilly and Finn may have gone too far even though he states that their lives are covered very well in “excellent biographies” but he then only cites a couple of magazine articles about them…hardly biographies of excellence, however worthy.

Mr. Falzini’s final format of 26 chapters presents some difficulties in sorting out the background of all the other major players in this extensive case. In general, he accords each person a chapter and these range in length from 16 pages to just a half page of only three paragraphs. The latter is that of Egbert Rosecrans, which is so brief his connection to the Lindbergh case is not even mentioned. Not all of the chapters profile people; Hauptmann’s auto and Lindbergh’s estate home merit their own chapters.

A few of the chapters have just not one individual but encompass a bevy of folks: the twelve jurors, the eleven NJ State Police personnel involved, and “The Experts”, consisting of Dr. Erastus Hudson (fingerprints); Arthur Koehler (wood scientist); Dr. Dudley Schoenfeld (criminal profiling); and Albert Osborn (handwriting.) Since the book contains no index, it is difficult to otherwise locate these individuals. Moreover, since Falzini praises these four men as the “founding fathers of forensic science”, it’s curious why he lumps them together (unindexed) into one chapter while the totally obscure Egbert Rosecrans enjoys his own separate chapter.

In another unusual grouping, Falzini combines the following trio (again, unindexed): John Hughes Curtis, plus a minister, Dean Dobson-Peacock, and an associate of Lindbergh’s, retired Admiral Guy Burrage. The latter two convinced Lindbergh to listen to the wild tales of Curtis, who falsely claimed he was in contact with the “real” kidnappers who had the baby on a Scandinavian ship. Lindbergh was on the last of the wild-goose chases with Curtis in Cape May, NJ when he was informed the corpse of his son had just been found. Curtis was ultimately convicted of obstruction of justice and sentenced to a year in prison and a $ 1,000 fine.

But whatever its shortcomings, this book contains a treasury of fascinating facts and photos, many of which have not appeared in prior books. For example, unlike the automobile of Bonnie and Clyde, which went on the vaudeville stage and then was exhibited in Nevada casinos for the next three decades, Hauptmann’s car was never exhibited. Instead, it was stripped of small parts, then the car body was crushed and recycled in a patriotic World War II scrap drive in 1943. Another example: the oldest surviving juror from Hauptmann’s trial, Ethel Stockton, lived until 2002. She died 67 years after the trial in her Florida retirement at the age of 100.

The author establishes the correct spelling of Lindbergh’s British maid, Violet Sharp, with no “e” on the end, as most Lindbergh books misspell it. Sharp committed suicide after forceful interviews by the police. Mr. Falzini affirms that her birth certificate says “Sharp” as do other official documents and she always signed her name that way.

One more interesting fact. For reasons that are unclear, the Lindberghs ignored William Allen when he was introduced to them as the person who found the corpse of their son. It may not have registered with them at the moment who Mr. Allen actually was and what he had done to help. Mr. Allen came across the remains by chance when the truck he was riding in stopped at a pullover in front of a wooded area on a rural road for him to walk a short distance to discreetly answer the call of nature. If he not been observant and curious, the remains may never have been found before Nature claimed them forever. But this African-American trucker ultimately obtained a reward of $5,000 for his discovery, even though it was not received until two years after Hauptmann was executed. The amount is equivalent to $95,000 in 2020.

Mr. Falzini remains neutral concerning the guilt or innocence of Bruno Richard Hauptmann. While he covers some of the trial testimony, as well as the evidence introduced, he derives no conclusion from either, instead leaving that decision to the reader.

Cemetery John by Robert Zorn (Overlook Press, 2012)

There have been nearly forty books written about the kidnapping and murder of the infant son of Charles Lindbergh. Most maintain Bruno Hauptmann was guilty, although he may have had help. A few proclaim his innocence. Still fewer argue the baby was not killed and grew to adulthood. But this is the first book to claim Hauptmann was assisted by two other men, neither of whom was Isidor Fisch (whom Hauptmann insisted gave him the ransom money.)

Zorn’s elderly father told him in 1980 that in 1932 he was present at a conversation involving the Knoll brothers, John and Walter, with “Bruno”, all three German immigrants in the Bronx. They spoke in German which Zorn did not understand but he heard one word in English, “Englewood.” The latter was a well-to-do suburb with many wealthy residents, including the mother-in-law of Lindbergh. John was a deli clerk who introduced teen-aged Zorn to stamp collecting and they socialized occasionally.

Decades later, Zorn’s father had studied the Lindbergh case and wrote Lindbergh a letter stating he had “convincing evidence” pointing to the identity of two other men who were involved in the crime with Hauptmann. Lindbergh dismissed the letter. On his father’s death bed in 2006, Zorn promised him that he would tell the world about John Knoll. That promise resulted in this book.

The author spent the next six years learning all he could about the Knolls, even traveling to Germany to interview relatives and others who knew them. Based on his exhaustive research, he came up with a host of coincidences supposedly tying them to the kidnapping. Examples: John once gave Zorn a “Lindbergh Airmail” stamp. John and Bruno had physical character traits in common and similar handwriting. The kidnapper who negotiated the ransom with Dr. Condon in Woodlawn Cemetery told Condo his name was “John.” (But why would any kidnapper give his real name?)

Zorn persists that three conspirators kidnapped the infant. Why three? Because the coded “signature” on each ransom note contained three nail holes. But of course it also contained two blue rings (two conspirators?) and one red center (lone perpetrator?) And in Zorn’s mind, it took three men to get the baby out the nursery window….one inside to hand over the child, another on the top of the ladder to receive him, and a third to steady the ladder on the ground. The author tracks the activities of the Knoll brothers and appears to demonstrate that they had plenty of money after the kidnapping. However, their assets certainly did not include any of the Lindbergh ransom money. Simple math proves this.

A three-way split of the $50,000 ransom leaves each man with just under $17,000. But when arrested in the fall of 1934, Hauptmann had almost $15,000 left. Yet he had not worked a day since the payoff in early 1932 but spent money lavishly, including a trip to Germany for his wife to check on his fugitive status, plus he lost a great deal in the stock market. It’s obvious there was no split…Bruno got it all.

Zorn wraps up his book with “Here is how I believe the crime unfolded:” In his fanciful tale, the evil trio arrived at the Lindbergh estate with the ladder in Bruno’s car. Bruno, with gun in pocket and carrying a gunny sack, walked in his stocking feet through the unlocked front door of the estate home. Unseen and unheard by Lindbergh, his wife, their three servants, and their dog, Bruno went upstairs to the nursery. He silenced the baby, put him in the sack, and left a ransom note. He passed the baby out the window to John who had climbed the ladder, while Walter held the ladder steady. The baby was dropped accidentally on the way down the ladder, suffering a fatal injury.

Bruno made his way back to the first floor, again unseen and unheard, left by the front door, retrieved his shoes, and joined his two companions. They drove off, removed the nightwear from the baby, dumped the infant’s body the first chance they got, and then continued back to the Bronx to begin negotiation for the $50,000.

So why did Hauptmann refuse to name his co-conspirators and save his own life? Zorn believes Bruno was afraid the Knolls would harm his wife and child. Of course, had they been arrested too, they would obviously never have been in a position to harm anyone.

New Jersey’s Lindbergh Kidnapping and Trial by Mark W. Falzini and James Davidson (Arcadia Publishing, 2012)

This compact, soft-cover book totals just 127 pages but encompasses over 200 photographs and illustrations. Its introduction is based in part upon the New Jersey State Police Museum Teacher’s Guide, published by the State Police Memorial Association in 1996. The two authors could not be more qualified to illustrate and illuminate this famous case. Mr. Falzini has over 20 years of experience as the archivist for the New Jersey State Police Museum, whose holdings now include over a quarter of a million documents, photos, and videos about the Lindbergh case. Davidson is a New Jersey historian who grew up in Flemington, New Jersey and currently lives near the former Lindbergh estate. (The Lindberghs only briefly lived in the home after the kidnapping and donated it in 1940 to the State of New Jersey.) He has one of the largest private collections of Lindbergh memorabilia and was the source of a significant number of illustrations in this book.

It is important to understand that this book is part of the “Images of America” series by Arcadia which specializes primarily in photographic historical books in which nearly all of the short bursts of text describe or explain a photograph or illustration. While all of these are divided into seven different chapters, the book contains no index, which limits its usefulness to readers and researchers. But this minor weakness in no way detracts from its vast panorama of period photographs and illustrations of pertinent charts, posters, news clippings, ransom notes, sketches, etc. which abound within its covers.

Virtually all of the famous and traditional photos of Lindbergh, Hauptmann, and the principals of that 1935 trial are included, as well as the missing person flyer of Charles Lindbergh Jr. But many of the pictures and other illustrations have not been seen in print since their first appearance in mid-1930s. These include one of William Allen, the African-American local worker who discovered the corpse of the abducted baby; two of Isidor Fisch (whom Hauptmann claimed gave him the ransom money); and also one of Hauptmann’s wife and his mother, hugging in Germany.

There are a wide variety of pictures relating to the crime and the trial: formal photographs, snapshots, candid ones by the media, and personal photos by relatives. The identity of those in the illustration are set forth, as well as their significance to the kidnapping, the investigation, or the trial. Usually the captions are two or three sentences, but a number them have a longer explanation.

Despite the relatively sparse text in this book, it includes many factual nuggets that either shed more light on this case or amplify a now forgotten item regarding the baby’s kidnapping and murder. In the beginning chapter, we learn that Lindbergh’s initial date with his eventual wife, Anne Morrow, was the first date he ever had in his life. A few pages earlier, there is a facsimile of the ten- cent airmail stamp of 1927, issued in Lindbergh’s honor, depicting his airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis.

The chapter on the trial contains an unposed photo of Margaret Bourke-White with her camera in the courtroom. She was the first female photographer for both Fortune and Life magazines and ultimately the first female war correspondent in World War II. To emphasize the large volume of mail Lindbergh received after the kidnapping, the authors include a photo of his over-burdened mailman, who delivered four sacks of Lindbergh mail every day. In just one month the aviator received over 40,000 letters. There is also a candid shot of a lovely woman at the trial, sorting the papers of lead defense attorney, Edward Reilly. She is not named in the caption but the authors reveal coyly “…although married, Edward Reilly was known to attend the trial with a bevy of attractive secretaries (who) would mysteriously disappear when his wife would attend the trial.”

Neither Messrs. Falzini nor Davidson make any judgement regarding the guilt or innocence of Hauptmann. But they do afford the reader a fresh insight into “The Crime of the Century” by providing a visual and factual overlay to the case.

Hauptmann’s Ladder by Richard T. Cahill, Jr. (Kent State University Press, 2014)

This book, sub-titled “A Step-by-Step Analysis of the Lindbergh Kidnapping” has been praised as “the definitive examination of the Lindbergh case.” If true, the reader has a right to expect a comprehensive encyclopedia covering new insights, and/or previously unknown facts about, this complex crime. Alas, this does not happen. The vast majority of all the facts elaborated herein were already covered in previous books, including two by Jim Fisher (The Lindbergh Case and The Ghosts of Hopewell.) Much akin to Fisher, Cahill also points out the flaws and inconsistencies within the revisionist histories concocted by Anthony Scaduto and Ludovic Kennedy in their “Hauptmann’s innocent” books.

The publisher helps emphasize Cahill’s conclusion that Bruno Hauptmann kidnapped the Lindbergh baby by featuring a large grim photo of a defiant Hauptmann on the front cover. The author used his book title to nudge the reader into concentrating on one of the most significant piece of evidence in the trial: the perpetrator’s ladder. It was a home-made, collapsible one, consisting of three separate sections so disassembled, it was easily concealed in the backseat of the kidnapper’s automobile. Assembled at the crime scene, it comfortably reached the nursery window on the second floor of the Lindbergh family estate home.

Most of the materials used in the ladder were purchased from the Bronx lumber yard that Hauptmann frequented. Arthur Koehler, the wood expert from Wisconsin, testified and demonstrated at the trial that the ladder rails were planed with a hand plane belonging to Hauptmann. But one of the most damming evidentiary facts about the ladder is that one of the short boards on it was sawed off a board which was originally nailed to a crossbeam in Hauptmann’s attic.

So to believe in Hauptmann’s innocence, one has to be convinced that someone else with carpentry skills built this ingenious ladder. To do it, the materials must have been purchased from Hauptmann’s favorite lumber yard. Then someone had to secretly gain access to Hauptmann’s garage and use his hand plane to plane the rail edges. Finally that person would have to somehow enter Hauptmann’s attic, unseen and unheard, and saw off a piece of wood nailed to an attic crossbeam and then make that piece a part of the ladder.

Cahill does not ignore the veritable mountain of other evidence against Hauptmann….his handwriting in all the ransom notes, the nearly $ 15,000 of ransom bills hidden on his property, and his luxury life of leisure after the ransom was paid, despite never working again during the Great Depression. Dr. Condon, who spent an hour in a park negotiating with the kidnapper, identified him, as did a cab driver who was stopped by the kidnapper who paid him to deliver another ransom note to Condon. The author does provide one nugget of information not found in prior books, which drew a blank regarding the source of Condon’s claimed doctorate. Cahill reveals Condon received a PhD in pedagogy from New York University in 1904.

The closing pages of the book provide details on what eventually happened to most of the principals in this case long after the trial, following some of them to their death bed. The wives of both Lindbergh and Hauptmann lived into their 90’s, in an era when life expectancy was two decades less. Cahill also tells of the subsequent careers of the defense and prosecution attorneys, the trial judge, Col. Schwarzkopf, as well as the main witnesses in the trial.

OTHER BOOKS ABOUT THE LINDBERGH CASE

- The Great Lindbergh Hullabaloo by Laura Vitray (William Faro, 1932)

- True Story of the Lindbergh Kidnapping by John Brant & Edith Renaud (Kroy Wen, 1932)

- The Lindbergh Crime by Sidney B. Whipple (Doubleday/Doran, 1935)

- Jafsie Tells All by Dr. John F. Condon (Jonathan Lee, 1936)

- The Crime and the Criminal by Dr. Dudley Schoenfeld (Covici/Friede, 1936)

- The Hand of Hauptmann by J. Vreeland Hardin (Hamer, 1937)

- The Trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann by Sidney B. Whipple (Doubleday/Doran, 1937)

- The Lindbergh-Hauptmann Aftermath by Paul H. Wendel (Loft, 1940)

- Where My Shadow Falls by Leon Turrou (Doubleday, 1949)

- Aspects of Murder by Harold Dearden (Staples Press, 1951)

- The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case by Ovid Demurs (Monarch Books, 1961)

- Hysteria: The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case by Andrew K. Dutch (Dorrance, 1975)

- In Search of the Lindbergh Baby by Theon Wright (Tower Books, 1981)

- Crime of the Century by Gregory Ahlgren & Stephen Monier (Branden Books, 1993)

- Loss of Eden by Joyce Milton (Harper Collins, 1993)

- Lindbergh, The Crime by Noel Behn (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1994)

- Murder of Justice by Wayne Jones (Vantage Press, 1997)

- The Case That Never Dies by Lloyd C. Gardner (Rutgers University Press, 2004)

PART THREE: MOTION PICTURES AND DOCUMENTARIES

MOTION PICTURES OF INTEREST

The Spirit of St. Louis | Warner Brothers Pictures. | 1957

135 minutes | Drama

Starring Jimmy Stewart as Charles Lindbergh. Available as a DVD, and may be available On Demand or on Television networks that show older motion pictures.

Presents the Hollywood version of Lindbergh’s life leading up to the famous transatlantic flight and the flight itself. Mr. Stewart was in his 40s when he played this part, about 20 years older than Charles Lindbergh, but with the help of weight loss, hair dye, and special effects the motion picture is realistic enough for its era. Coincidentally, one of the supporting actors, Murray Hamilton, would appear again with Mr. Stewart two years later in The FBI Story as FBI Special Agents.

The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case | Columbia Pictures | 1976

NBC

148 minutes | Drama

Is available online or On Demand.

This was a made-for-television motion picture first broadcast in February 1976. Contains name actors and is a good quality production. Most notably, Bruno Richard Hauptmann was played by none other than a young Anthony Hopkins, using his best German accent. Mr. Hopkins received an Emmy for his work in this film, and would go on to have a storied career as an actor. Interestingly enough, one of Sir Anthony’s most famous subsequent roles would be as the horrific Dr. Hannibal Lecter in three well-known films: The Silence of the Lambs, Red Dragon, and Hannibal.

DOCUMENTARIES OF INTEREST ABOUT THE LINDBERGH CASE

Who Killed Lindberghs Baby?

PBS | 2013 | 54 minutes | DVD

Interesting and informative video about the case and theories surrounding it. Interviews of Mark Falzini, John Douglas, and others.

Across the Atlantic: Behind the Lindbergh Legend

National Geographic | 2009 | 55 minutes | DVD

Excellent video presentation and reenactment of the background story. Makes use of an exact replica of the Spirit of St. Louis aircraft.

Charles and Anne Lindbergh: Alone Together

A&E | 2005 | 100 minutes | DVD

Well-done presentation about the lives of the Lindberghs.

JACK FRENCH

A former United States Naval Officer and retired FBI Special Agent, has been studying this famous crime since 1962 when he interviewed the owners of the small Bellevue Hotel in Cape May Court House, New Jersey. Charles Lindbergh and an aide stayed there in April 1932 while pursuing a bogus story of the kidnapped baby being held on a ship in the nearby waters of the Atlantic Ocean. French has lectured on this topic many times in several venues, including presentations at the George Mason University OLLI program and the University of Delaware. He continues to research “The Crime of the Century” and recommends that those like-minded visit the Lindbergh Exhibit in the New Jersey State Police Museum and Training Center in Ewing Township, New Jersey.

ERNEST JOHN PORTER

A retired Unit Chief and Supervisory Public Affairs Manager at the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington, DC, Mr. Porter worked with authors, radio shows, motion pictures, television shows, documentaries, FBI History, lecturing, and special projects for the FBI for nearly 40 years. He is the developer, owner, and manager of FBIOGRAPHY.